“Programming is one of the rare disciplines in which you can create something from absolutely nothing. You can create whole worlds that behave exactly as you want them to behave. The only thing you need is a computer.” – Ivan Čukić, Functional Programming in C++

Introduction

I have a task set before me – one that’s as clear as imprecise. To assemble a list of the greatest works of a genre may seem a straightforward enough goal for a writer. Unless that genre is a Roguelike, of course.

Many have called their games roguelikes. Many games so called look nothing similar. How do I choose from the vast library those works that best represent the genre? The shelves stretch far into the shadows. To the times when phosphorous displays glowed weirdly in the darkness with their arcane letters of forgotten programming languages. When their light fell upon those masters of code, who were the first to bring to life the enchanted worlds, found before only upon the pages of fantasy books.

History travels by winding roads. The genre had no navigator to straighten its course, leading to an incredible multitude of inspirations and a fantastic array of unique ideas. The original features may seem almost lost among such startling variety, but not yet. There were many, recently, who’ve taken up the old banner, bringing back the traditional roguelike. Their guiding stars are: Procedural Generation, Single Hero, Turn-Based Combat and Grid-Based Movement. I’ll follow this definition, as far as possible.

Let’s not waste any more time on terminology, now that I have criteria, by which to make my choice. Without further ado, let’s leave our mundane world behind and set forth on a journey across the realms of Roguelikes.

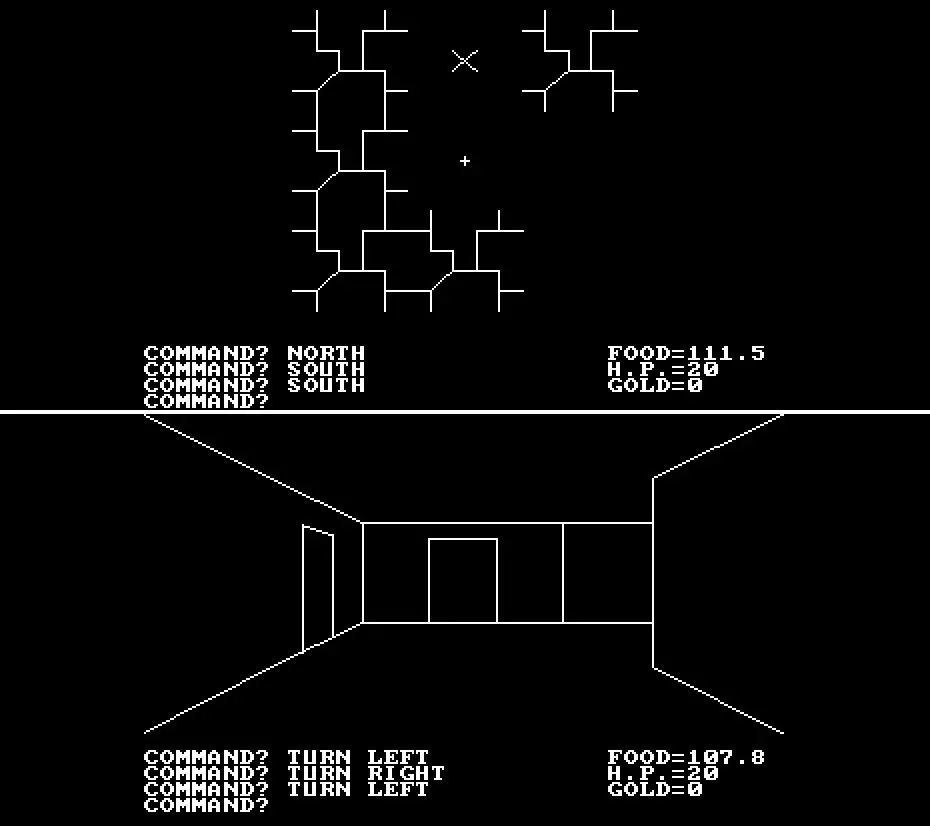

Akalabeth: World of Doom (1979)

What better place to start than here! – amidst the ruins of a once great and prosperous kingdom, during the first days after the end of a long war. The time of glory has passed – whether in battle or in peace. A time of restoration begins. The old heroes take a step back – but heroes are still in demand. The enemies, although defeated, are not all dead. They hide amidst the shadows of the dark places, biding their time. It’s now the player’s job to take up the sword and finish that which was started by Lord British himself – to cleanse the realm of evil, paving a road towards a new age of light.

I hope the reader will forgive me my, somewhat unexpected, choice. As Akalabeth is, by its mechanics – if nothing else, a true roguelike. Its world was procedurally generated, before the concept was popularized by Rogue and Hack. The combat is turn-based and movement takes place on a grid. It even has a hunger mechanic! Although, it looks different from those other masterpieces that came to define the genre. It has a fully graphical interface and a 3D-like perspective – one of the first uses of such in computer games’ history.

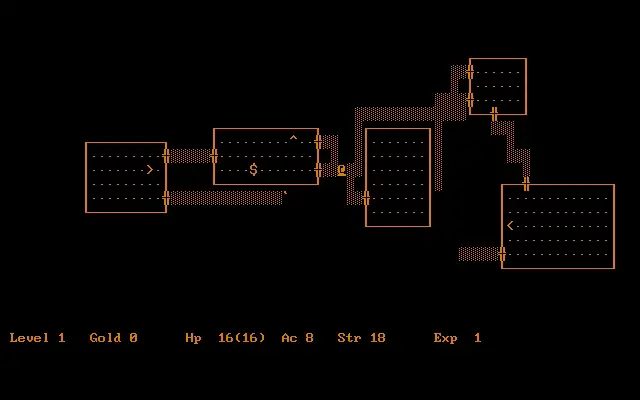

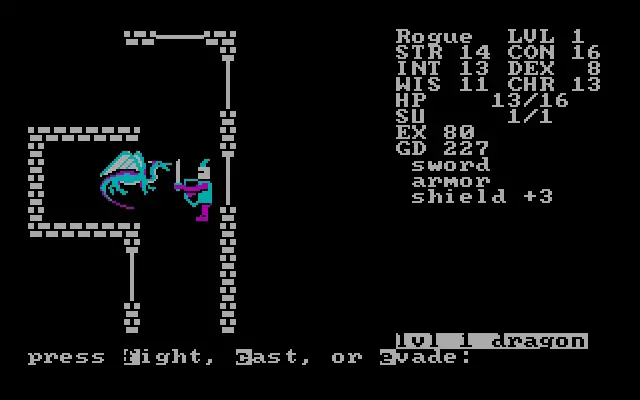

Rogue: Exploring the Dungeons of Doom (around 1980s)

At the lowest level of the Dungeons of Doom a mysterious item lies, known as the Amulet of Yendor. Strange and terrible creatures guard its magical secrets – goblins and trolls, vampires and wraiths and other things that made their lair in the shadowed halls. An enchanted blade, a potion of healing, a scroll with a spell written on it – these will be the lone hero’s companions on a quest through the dark depths.

Many would call Rogue the first Roguelike and not without reason. It achieved some degree of purity that made it stand out from other games of the time. Its gameplay is as straightforward as its basic ASCII interface. Its mechanics are simple and elegant – it’s turn-based, with movement done on a grid. It has a procedurally generated dungeon – but there is no complex algorithm – no lakes or special levels. It feels almost like a game of cards, with clear rules one can learn after a first try. This game is THE ROGUELIKE, as much as Doom is THE SHOOTER. It was innovative enough for the time, but it required no elaborate ornamentation to make it a true classic.

Dungeons of Moria, or just Moria (1983)

We now find ourselves in a poor and lonely town. A number of merchants here and there selling their wares. Drunks and beggars on the streets. Not the kind of place where one would expect to find battles and glory. There’s a stairway, though, somewhere in this town – leading deep underground. While the merchants’ wares are not of a regular kind. They sell shovels and torches, swords and spears, scrolls of spells and enchanted amulets. Seems like there’s adventure here, after all!

Dungeons of Moria is as similar to Rogue as it is different. It feels larger, more complex in its story and characters, while preserving the same simplicity of gameplay that made Rogue famous. The setting is well-thought-out, taken from Tolkien for the most part. There are characters, referencing the great writer’s work. There are hero classes and races the player can choose from. There are more varied spell mechanics. Even the dungeon itself looks and feels more complex, being deeper and with way more elaborate level design. Other than that, Moria is a classical roguelike with all the traditional features, standing at the foundations of the genre, next to Rogue.

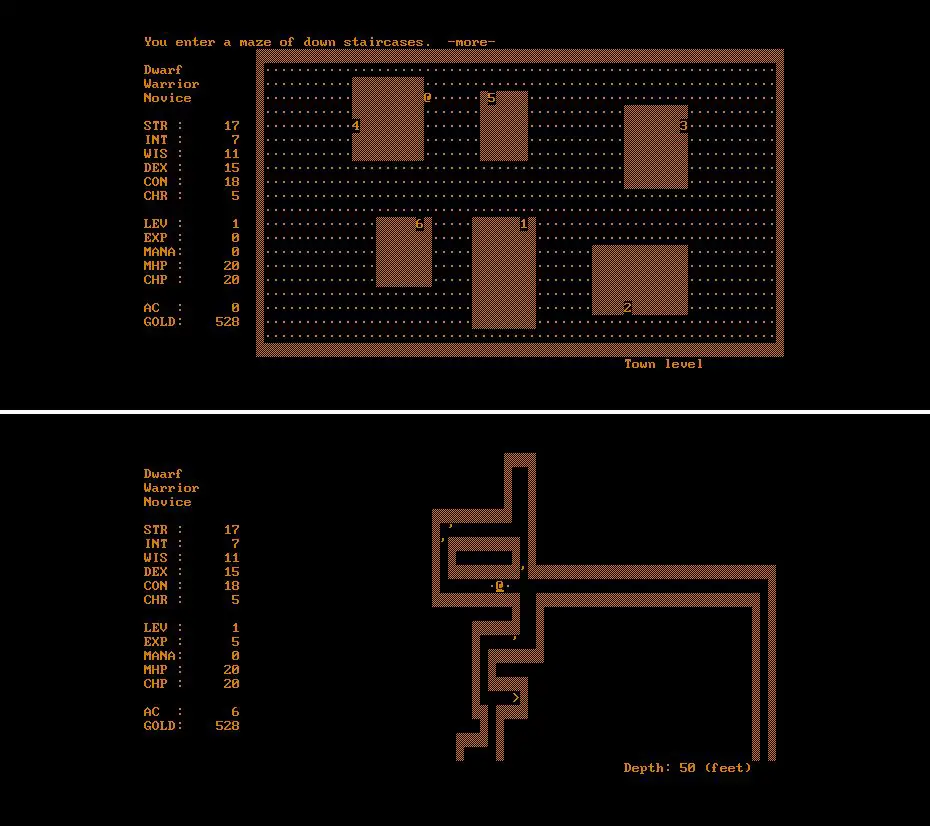

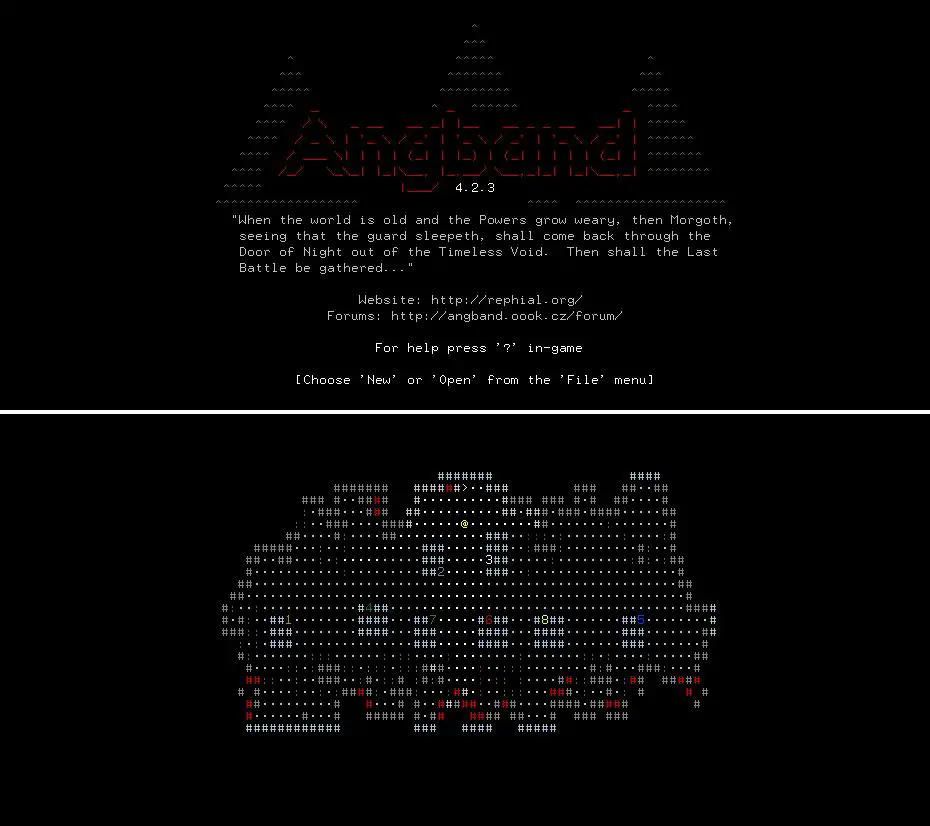

Angband (1990)

This game is to Moria – what Moria is to Rogue. It looks and feels similar, but is way more complex at the same time – the dungeon is deeper, the items and monsters are more varied. The story, however, is almost the same. A desolate town under which an ancient dungeon slumbers – home to strange, forgotten creatures, hiding from the light in its forlorn depths. Angband is another name taken from Tolkien‘s immortal writing – a place of shadows, the fortress of the great enemy – Morgoth, the lord of all that is evil. He’ll be the final adversary you meet, waiting in darkness, on the hundredth floor of the dungeon.

The main mechanics, too, are much the same here. Angband is based on Moria’s code, after all. Of particular note is the history of the making of this game. It was created and is maintained by a number of developers, from all over the world. This approach soon became somewhat of a unique tradition in the genre. It also led to an amazing variety of Angband Variants, with the game becoming, in a sense, one of the first example of what we may now call an engine. Tales of Maj’Eyal – one of the most famous modern roguelike began as one of Angband‘s variants.

Larn (1986)

Time waits for no mortal. Only by sorcery can its course be sometimes altered. You’ve heard rumors of enchanted scrolls containing such spells. Yet, no one knows of magic powerful enough to halt completely its unceasing run. While the few months you’re given are running out. You must travel now – to a town, hidden among the wilderness. Under the floors of its shops, a mysterious dungeon lies. The caverns of Larn. Its guards are many – demons and goblins and other evil creatures. You must buy whatever supplies you can with the few coins you’ve saved, and then brave its grim depths. There’s no other choice and no time to waste.

Larn is another roguelike, along Omega, which I’ll cover later, that never got the fame it deserves. It did many things first, and it did them well. It has a town level, offering more variety in its businesses than that of Moria. It also has two distinct dungeons. Each feels completely unique and offers different challenges. As is traditional for the genre, there’s also a great array of items: scrolls, potions, weapons and other things an adventurer may need on their quest. With all that, Larn is still a traditional roguelike, in the style of the original Rogue. From its ASCII graphics to its turn-based grid-based gameplay and procedurally generated dungeons.

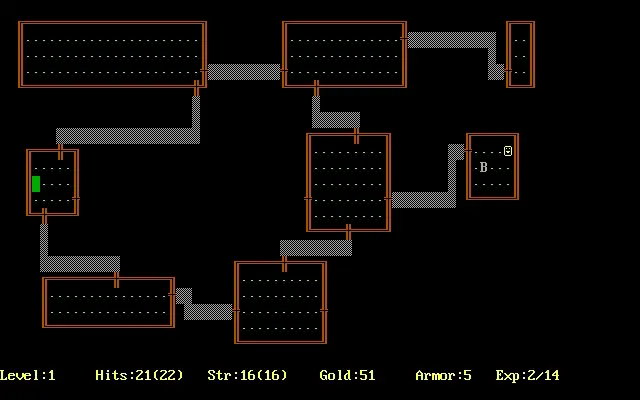

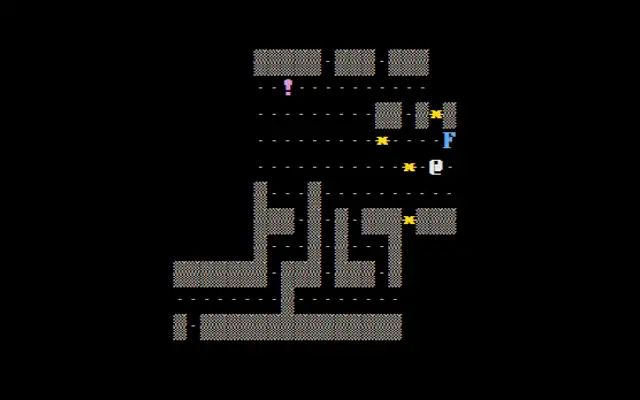

Hack/Nethack (1984, with development still active)

Hack looks very much like Rogue at a first glance. There are no winding tunnels of Moria and Angband – no town, offering a brief respite to a tired adventurer. Well, not on the first level, at least. The hero’s quest is also the same as in Rogue. Get to the lowest level, find some legendary amulet and return with it to the surface. The formula is the same here – just as Rogue, Hack needs no complex embroidery to achieve that certain level of style and gameplay that made it one of the most well-known games in the genre.

It doesn’t replace the traditional mechanics, trying to be unique, but it stands out nonetheless. Everything is deeper here, somehow – more elaborate, without becoming too complicated. There are more items, more variation in the dungeon design, more types of enemies. There’s more you can do, interacting with the environment with a degree of freedom that comes startlingly close to a D&D session, when the dungeon master is ready to hear any mad idea that comes into your head. It can be argued, and not without good reason, that no other game has achieved this since.

Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup, or just Crawl (1995 for the original Linley’s Dungeon Crawl, 2006 – DCSS. Development still continues.)

Beware, mortal champions! Eldritch gods inhabit this place of doom and peril. By their word, your deeds shall be judged. Their will shall be your law, their wrath – your undoing. Well, unless you choose to go your own way. If this isn’t already clear: Crawl has many gods. Some are honorable and majestic. Others – sinister and macabre. Yet others are weird and uncanny, with unpronounceable names, in the best traditions of Lovecraftian mythos. Each offers unique advantages or disadvantages to their worshipers.

Along with its awe-inspiring pantheon, Crawl offers an incredible selection of hero species and classes, not only in how large it is, but also how unique. I haven’t yet heard of another game, where one can play as an octopus wizard, worshiping the god of slimes. Nevertheless, Crawl still preserves the traditional mechanics of a classic roguelike, being turn-based and grid-based. It also has great procedural generation algorithms, used to build its single, though amazingly complex, dungeon.

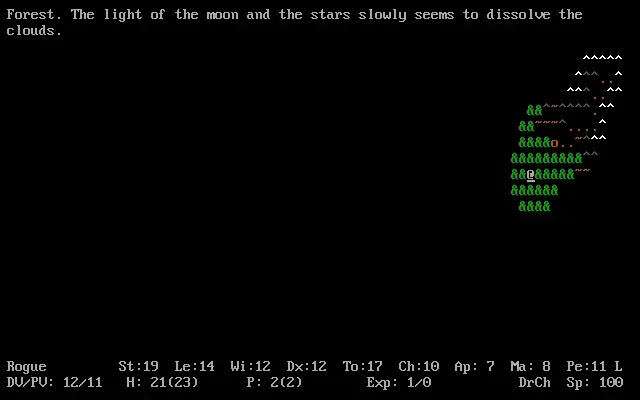

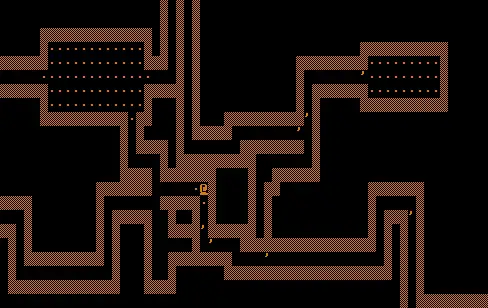

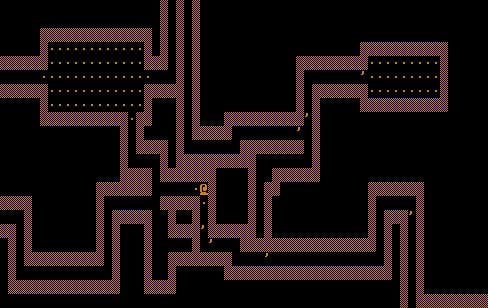

Ancient Domains of Mystery, ADOM (1994)

From the black depths at the roots of the mountains, from the caves and hollows of the cliffs of the Drakalor Chain, Chaos spreads. Many an adventurer has entered the region, searching for its source. Some were driven by their desire for glory – others by their lust for power. They bought supplies at the humble village of Terinyo. Spoken with rogues and thieves at the outlaw settlement of Lawenilothehl. They’ve traveled through forests and hills, crossing the great river on their way westwards. The closer they got to their goal – the more dangerous the land became. They fought or ran, and some have never reached their destination – The Caverns of Chaos.

If Nethack feels like a single dungeon from D&D – then ADOM gives you an entire realm to explore. Like the former, ADOM is a classical roguelike. It even looks very much like Rogue with its single-screen floor layout. The combat is turn-based, movement’s done on a grid. There’s the great main dungeon too, as is traditional for the genre. However, there is so much around it! Towns, forests, hills and other, strange and mysterious places. If you’ve ever played the original D&D adventures: The Temple of Elemental Evil, The Keep on the Borderlands or even Ravenloft – then you know what I’m talking about. This is what ADOM is like. It achieves a level of world-building rivaling that of the great role-playing classics, while preserving the essence of a true roguelike.

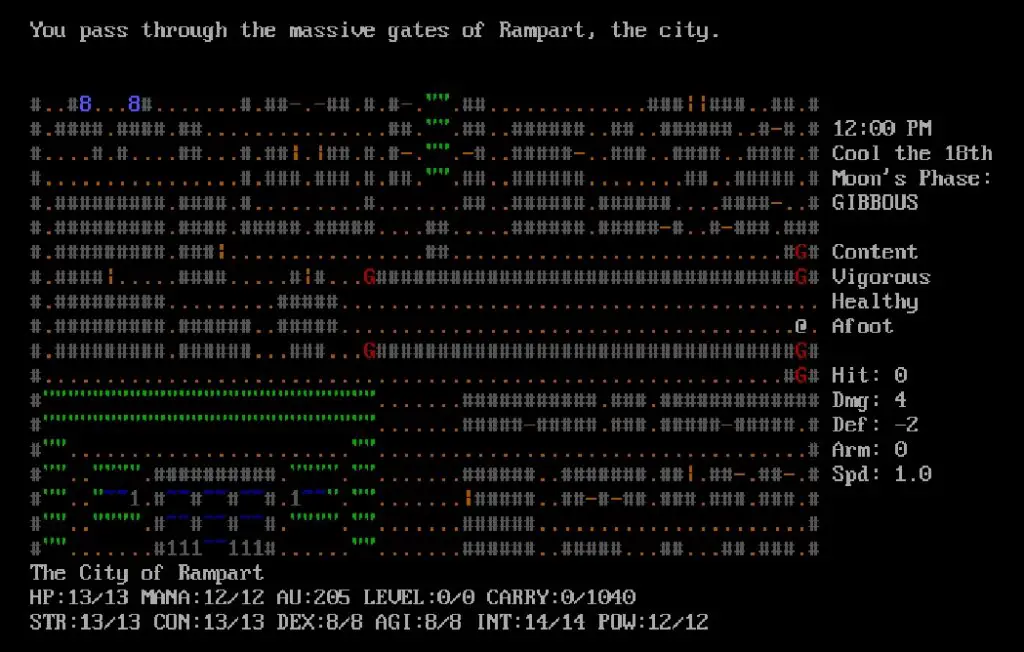

Omega (1987)

Sorcerous winds howl above the Sea of Chaos. They surge over the towers and walls of the ancient city of Rampart. They fly through its labyrinth of crooked streets with their shops and bars, universities and casinos. Druids and magicians listen to its arcane whispers. The winds pass by the guards at the massive gates and a lonely adventurer, who just entered the town, may hear strange voices in the air. It’s never too late to turn back and brave the wilderness instead.

Omega is certainly one of the most ambitious games of the time. Its main town is way more complex than that of Moria, Angband or Larn. Even today it may be hard to rival its vast selection. The game also features a large wilderness area that can be placed next to that of ADOM, that was released years later. Just like that other game, Omega also has a deep well-thought-out setting, where Chaos plays an important role. It feels different from ADOM, however, even though these are both pure classical roguelikes with traditional mechanics. Omega seems more chaotic – not only in its story. Some of its mechanics are unique to the point of being almost incomprehensible to a regular player. It’s also one of the most difficult games on the list, where you’re given no help along the way and no clue of where to go next.

Telengard (1978 – the first version)

Another night at the inn. A chance to bind the wounds and sharpen the sword. The blade is covered with strange runes, glowing weirdly in the dim-lit hall – enchanted it certainly is. You look once more at the other items you’ve found on your journeys, laying on the table in front of you. A ring of protection, a scroll of rescue. These’ll come in handy, no doubt. You’ve learned a lot on the last trip. You’ll now know better than to cast a sleep spell on a vampire. The undead don’t sleep. Beware the traps, too – you tell yourself as you put yet another bondage on your arm. As morning comes you’ll descend once more. Into the depths of Telengard.

Well, I started with an unexpected choice – so let me end with one also! Here, though, I’ll have to argue, just a bit, to defend my selection. While Telengard has procedural generation and grid-based movement – there is a time-limit on the hero’s actions. Yet, bear with me on this one! If I turn on the time-limit in HoMM or Age of Wonders, do they become different games? Is chess any less turn-based if it’s played with clocks? The mechanics are still the same – that feature in Telengard adds a sense of urgency, but doesn’t change the underneath logic. It’s a matter of degree – you are given enough time for the game not to feel reflex-based in the slightest. To me, Telengard is a Roguelike, from its mechanics to its atmosphere, and one of the first ones, at that.

Conclusion

We, as humans, also play a time-restricted game, so let’s not waste too many turns arguing. I hope you enjoyed this reading, as over-the-top as it may seem sometimes, even to its author. I also hope I’ve surprised you with some of my choices on this list, and that, maybe, you’ve discovered some game you’ll want to try now.

Thank you for reading this, in any case! I plan to write a second and, perhaps, a third part at some point. Here, I’ve mostly concentrated on the classics. I’ll look at some of the more modern games in the later parts. Have a nice day, or night, or whatever time it is over there – on the surface. It’s hard to keep track of here, in the Dungeons of Doom.

Nice article, waiting for the next parts! 🙂

There are some other roguelikes before Rogue: Beneath Apple Manor (1978), some also consider Star Trek (1971) one.

> “This game [Rogue] is THE ROGUELIKE, as much as Doom is THE SHOOTER.”

Not sure about this — the parallels between roguelikes, first-person shooters and metroidvanias go as follows:

Games which defined the genre: NetHack/Angband; DOOM; Metroid/Castlevania SotN

Games which inspired the games above: Rogue; Wolfenstein 3D; Zelda

So I would argue that NetHack is for roguelikes what DOOM is for first-person shooters. Contrary to “Doom clones” and “metroidvanias”, people called the genre after what they thought was the first game in the genre (they did not know BAM), not the games popular at the time.

Thank you! I really appreciate your response. You bring up some very interesting subjects, concerning the history of the genre. I may have to address these in the next part.

However, I compared Rogue to Doom not just for historical reasons. The two games appear similar in how pure and straightforward their mechanics are, and how influential they’ve become.

There is no mechanic in Rogue that is not a roguelike mechanic. No towns, no stores, no allies. Same for Doom. NetHack, however, adds many features that are not essential for a game to be called a roguelike.

Still, you make some great arguments, and I’ll have to think more about this before I start working on the next part.

By this metric, I think you should compare Rogue to Wolfenstein 3D, not DOOM? I believe Wolfenstein 3D is pure already, it has all the essential features of a first-person shooter and no extras. DOOM is pure too, but younger.

Today the roguelike community seems to have a rather stable opinion of what a roguelike is. But some earlier definitions included some weird stuff, e.g., features that were more like NetHack/Angband than Rogue. Since then we have seen lots of new games, and we have seen which elements can be removed from the game while it still has this elusive roguelike feeling, and which ones cannot be removed, making the understanding (inside the main roguelike community) more stable.

Rogue has potions with randomized names. I have seen people considering this an essential roguelike feature, but there are lots of roguelikes which do not. So is it essential or not?

Angband, NetHack, and many more roguelikes are extremely complex games, and some people include complexity in their lists of roguelike features (e.g. it is included in the Berlin Interpretation). But Rogue is not that complex.

I would consider shops, race/class selection, rumors, etc. to be roguelike features (they all appear in both NetHack and Angband, as well as in many other roguelikes) but Rogue lacks these either.

Around 2005, lots of people making roguelikes would try to create extremely complex games, more in style of “NetHack/Angband but bigger” than Rogue. They would include randomized potions, shops, race/class selection, towns, allies, etc. Then the 7DRL Challenge started and caused a shift toward simplicity.

Concerning Doom: I compared Rogue to a famous pure shooter to emphasize how undiluted its mechanics are. I could’ve as well compared it to Quake. I don’t think it’s as well-known, though.

Concerning the Roguelike definition: The one I’ve used in the article is somewhat of an intersection of the others. If I extend it any further, I may have to exclude Rogue itself from the list!

In any case, let us not argue about the genre’s definition! It’s a long and unthankful labor. You seem to have a good grasp of the genre’s history, though. Maybe we can talk more about it on Twitter or Discord?

Sure! If you have any questions, I will be happy to answer on Twitter or Discord 🙂

No part 2?